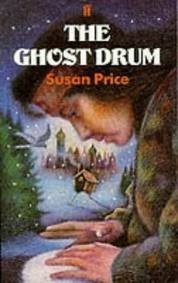

The Ghost Drum

Chapter One

In a place far distant from where you are now grows an oak-tree by a lake.

Round the oak's trunk is a chain

of golden links.

Tethered to the chain is a learned

cat, and this most learned of all cats walks round and round the tree continually.

As it walks one way, it sings

songs.

As it walks the other, it tells

stories.

This is one of the stories the

cat tells.

My story is set (says the cat) in a far-away Czardom, where the winter is

a cold half-year of darkness.

In that country the snow falls deep and lies long, lies and

freezes until bears can walk on its thick crust of ice. The ice glitters on the snow like white stars in a white sky! In

the north of that country all the winter is one long night, and all that long night long the sky -stars

glisten in their darkness, and the snow- stars glitter in their whiteness, and between the two there hangs a shivering curtain of cold twilight.

In winters there, the cold is so fierce the frost can be

heard crackling and snapping as it travels through the air. The snow is so deep that the houses are half-buried in it, and

the frost so hard that it grips the houses and squeezes them till they crack.

My story begins (says the cat) in this distant Czardom, on

Midwinter Day: the shortest, darkest, coldest day, followed by the longest, darkest, coldest night of the whole year.

On this day-night, this night-day, a slave-woman gave birth to a baby.

The woman lived with her husbands family in a small wooden house. At the centre of the house was a big, tiled stove. All day long a fire burned in the stove and sank its heat into the tiles. All day, and all night, the hot tiles gave their heat back to the house. At night the family spread their blankets on top of the stove, and slept there. With them, on the stove's top, tired and warm, the woman lay with her baby. Of them all, only the mother lay awake, as the night grew colder.

The slave-woman lay listening to the tiny sound, humming like the singing of a

cracked cup, that the stove made as it breathed out its warmth. She heard the deep, sleeping breathing of the family around her, and the frost snapping about the roof.

'If only I had been born the Czar's daughter!' said the

slave-woman to herself. 'Then my baby would be an Imperial Princess and all her world would be warm, safe and rich...But

I was born a slave's daughter, so my baby is a slave and she won't even own herself.'

That made her so sad that the tears began to run from her

eyes. She thought, 'I have laboured like a she-donkey so my master, the Czar, can have another little foal to work

and kick and sell as he pleases. I wish that neither I nor my baby had ever been born!'

Something struck the outer door of the house then.

The door boomed at the blow, and the warm air of the house quivered among the roof-beams and round the walls. The

slavemother jumped with fright; but none of the sleepers near her missed a breath.

From outside, where the frost crackled, a throaty, rough

voice called, 'May I come in? You in there! Say - may I come in?'

The family slept, unaware, as if the knocker at the door was

in the mothers dream, andher dream only.

Another booming blow was struck at the door, and the

slave-woman cried, 'Come in, and welcome!' For who knew? It might be a traveller lost in the snow, and needing

shelter.

She heard the outer door of the house open, and slam shut.

Raising her head, she looked down from the stove-top and saw the inner door fly open. In hurried a tall figure,

hidden under a big fur hat and a long, quilted, padded, fantastically embroidered coat. Bulky, beaded and patterned Lappish boots were on its feet, and large Lappish gloves on its hands. Over its shoulder was slung a flat drum.

This tall, odd figure crossed the room and climbed up to sit beside the young mother on

the stove. None of the sleepers woke. The stranger whipped off the fur hat, and the mother saw the face of an ancient woman, a face criss-crossed with wrinkles like fine old leather that has been crumpled in the hand. A thin beard of long white hair grew from the old womans chin, though her pink scalp could be seen through the white hair on her head. In the heat of the little house, the old woman opened her thick, padded coat, showing a tunic of leather beneath, decorated with beads and feathers. she pulled off her large gloves. She smiled at the young mother. Her few teeth were black or brown, with large spaces between them.

'A good night to you, daughter,' said the old woman. 'I've

come a long, cold journey to congratulate you on the birth of a fine child.'

The young woman hugged the baby tight. this was a witch,

come in the night as witches did come, to steal her baby and roast and eat it. She began to call out the names of

her family, hoping they would wake her from this dream, or wake and drive the witch away; but they slept as if not a sound had been made.

'Daughter,my little one,don't be

afraid,' said the witch. 'I've not come to hurt you or your baby, but to tell you this: the

baby you hold in your arms is the child whose birth I have been awaiting for a hundred

years.'

The mother opened her mouth softly, as if she would

taste the witch's words. Her baby's birth expected for a hundred years? What was her baby,

then? A saint-to-be? Would there be candles lighting churches for her baby a hundred years from

now?

'Give her to me,' said the witch. 'Let me raise her. Then she will be a Woman of Power, and the son of a Czar will love her. Keep her and raise her yourself, and she will be a slave and a mother of slaves, nothing more. Give her to me.'

The mother clung to her baby

and shook her head.

'You see the Ghost-drum on my back,' said the ancient

woman. 'You know by that I am a shaman. I can shift my shape and follow the dead to their

world. I know all the magics, and am a Woman of Power, yet I was born a slave too. On the night

of my birth, a shaman came to my mother and begged me from her. The shaman raised me as her

daughter, and gave me a gift of three hundred years of life. For a hundred years now I have

beaten my drum every day, and asked the spirits to tell me when and where my

witch-daughter would be born. This is the night: your child is the child. Give her to me. In my

care she will never be hungry or frozen or cruelly treated; She will not be a slave. Give her

to me, and she will be free; she will have power."

Tears wetted the slopes of the mother's face and neck. 'I cannot,' she said. 'My baby doesn't belong to me. I am a slave, her father is a slave, and she and we belong to Czar Guidon. If I gave you the baby, we would be whipped for giving away our master's property. We should be executed for stealing from him.'

The old woman hopped down from the

stove and hurried to the door, which opened before she reached it, and slammed after her. The

mother heard the outer door open, and slam too; and she lay quietly in the dark. with tears

running over her face, wondering if the witch had gone away. But the doors opened and slammed again, and the witch came back. She carried a snowball as large as her head. She sat on the stove and shaped the snow in her hands, and it didn't melt.

As her strong, wrinkled hands, with their sharp,

shifting bones, worked at the snow, the witch sang. Her voice travelled warm and humming

through the dark, and seemed to set motes of darkness spinning. Lengthening, the notes of her

voice rose into the rafters; and the young mother became calm and content as she

listened.

The witch shaped the snow like

a baby. 'Mine is a cold, pale baby.' said the witch. 'I have sung a spell into this snow, and

even if you put it into the fire, it will not melt until summer comes again. When I have gone,

and have taken my foster-daughter with me, you must show this snow-baby to your family

and say that it is your baby's dead body. No one will be surprised. Many babies die in

winter. They will take the snow-baby away and bury it, and no one will see it melt in the

earth when summer comes. You won't be punished because a slave-baby died in a hard

winter. Now give me your baby and take this one of snow.'

The mother brought her baby from beneath the covers,

but still clung and hesitated. The witch laid hands on the baby. 'Come; have sense and give her

to me. Keep her, and you keep her enslaved.'

The mother released her hold

on the baby, and the witch pressed it to her own chest, refastening her thick coat, so the baby

was fastened inside. The cold snow-baby, the witch put into the mother's

arms.

Then the witch jumped down from the stove, put on her

fur hat and her big gloves, cried, 'I wish you well,' and rushed to the door. The door flew

open, and the witch was gone through it. The young mother pushed herself up on one elbow to see

the last of the witch, but saw only a closed door, and heard nothing more than the slamming of

the outer door, and the crackling of frost about the house.

The snow-baby lay chillingly

cold against her. Before the night was over the mother couldn't remember if she had given her

daughter to a night-visiting witch, or if the cold baby she held was her own baby frozen to

death, and all the rest a dream.

So uncertain was she that she told no one about the

witch, but only that her first child, a daughter, had died a few hours after birth, in the

coldness of a winter night. But all her poor life the woman remembered the witch, and hoped

that she had been no dream.

'The Ghost Drum' is now available on Kindle. Click here for Kindle UK and here for Kindle USA

Its sequels, 'Ghost Song' and 'Ghost Dance' are also available.

To return to home page, click here.

To find other extracts, go here