In this third post about witches, I’m considering some children’s books in which the characters are recognisably witches, but good rather than evi

All of these examples are modern. I’m not sure I know of any good witches in older fiction except

for Glinda in ‘The Wizard of Oz’,and incidentally, I don’t know how I forgot to mention the Wicked Witch of the West, in my first witchy post, as a fine example of an American witch – and her

recent reinvention by Gregory Maguire in ‘Wicked’ exemplifies the changes in attitude which have been taking place over the decades, changes which have to be set down to the feminist

movement. The very title of Maguire’s book is a gauntlet thrown down. If anyone is wicked in ‘Wicked’, it’s not the witch. And it’s a lot more difficult these days than it used to be,

to think powerful female = witch = evil.

Let’s start with the great Terry Pratchett. The very first book of his I ever read was ‘Wyrd Sisters’. I’d been put off

the Discworld novels by their covers, which looked too hysterical for me. But I picked up ‘Wyrd Sisters’ in the library one day and read the opening page:

The wind howled. Lightning stabbed at the earth erratically, like an inefficient assassin...

…In the middle of this elemental storm a fire gleamed among the dripping furze bushes, like the madness in a weasel’s eye. It illuminated

three hunched figures. As the cauldron bubbled an eldritch voice shrieked: “When shall we three meet again?”

There was a pause.

Finally another voice said, in far more ordinary tones: “Well, I can do next

Tuesday.”

On this comic anticlimax we meet Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg and Magrat ('Margaret', only her mother couldn’t spell). And

what these three witches do is what women down the years have always done. They help bring babies into the world, they do their best to cure the sick, they lay out the dead, and they

dispense commonsense advice with a bit of magical flimmery-flammery to help it along. On top of that, Granny Weatherwax in particular is skilled in what she calls ‘headology’ – a fine-tuned

sympathy with the minds and beings of others. In ‘Wyrd Sisters’ the three witches prevent soldiers from killing a baby on the moor at night, and on discovering a crown in the bundle of wrappings,

realise they have to hide the child. And the crown? Can it be hidden too?

“Oh, that’s easy,” said Magrat. “I mean, you just hide it under a stone or something…”

“It ain’t,” said Granny. “The reason being, the country’s full of babies and

they all look the same, but I don’t reckon there’s many crowns. They have this way of being found, anyway. They kind of call out to people’s minds. If you bunged it under a

stone up here, in a week’s time it’d get itself discovered by accident. You mark my words.”

“It’s true, is that,” said Nanny Ogg earnestly. “How many times have you

thrown a magic ring into the deepest depths of the ocean and then, when you get home and have a nice bit of turbot for your tea, there it is?”

They considered this in silence.

“Never,” said Granny irritably.

The Discworld novels are written for adults, but are YA in their appeal, and Terry Pratchett has also written several children’s books

set in the same world, featuring the young apprentice witch Tiffany Aching – a girl of great grit, determination and courage. The first in the series is ‘The Wee Free Men’, and begins with

yet another witch (Miss Perspicacia Tick) sitting under a hedge in the rain, making a device to ‘explore the universe’:

The exploring of the universe was being done with a couple of twigs tied together with string, a stone with a hole in it, an egg, one of Miss Tick’s

stockings which also had a hole in it, a pin, a piece of paper, and a tiny stub of pencil. Unlike wizards, witches learn to make do with very little.

Terry Pratchett, you feel, actually likes women. He seems comfortable around them in a way the male authors of my last

week’s post – C.S. Lewis, T.H. White and even Alan Garner – do not.

In Philip Pullman’s ‘The Golden Compass’, the first book of ‘His Dark Materials’, we meet a race of witches of a very different type.

They are far wilder and more romantic than Terry Pratchett’s – a reversion to the witch queen type, in fact, but as ever-youthful as the fairies and as warlike as the Amazons. They come to

the rescue of Lyra and her friends during the attack on the Bolvangar experiment station, shooting their arrows with deadly effect:

“Witches!” said Pantalaimon.

And so they were: ragged elegant black shapes sweeping past high above, with a hiss

and swish of air through the needles of the cloud-pine branches they rode on. As Lyra watched, one swooped low and loosed an arrow: another man fell.

A few pages later, Lyra meets one of them: clan queen Serafina Pekkala:

She was young – younger than Mrs Coulter; and fair, with bright green eyes; and clad like all the witches in strips of black silk, but wearing no furs,

hoods of mittens. She seemed to feel no cold at all. Around her brow was a simple chain of little red flowers. She sat on her cloud-pine branch as if it were a

steed…

Lyra could see why Farder Coram loved her, and why it was breaking his heart… He was

growing old: he was an old broken man, and she would be young for generations.

They aren’t central characters, and you could argue that Mrs Coulter wears the pointed hat in this story, but the courageous,

nearly immortal witches, with their necessarily brief liaisons with human men and women, lend an exotic touch of wildness and tragedy to Pullman’s world.

A witch who didn't make it into the last couple of posts is the Russian BabaYaga, with her hut on chicken legs. She's pretty scary

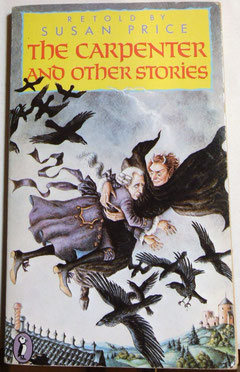

but ambiguous - she can actually be helpful if propitiated in the right way. Susan Price’s Carnegie Medal winning ‘The Ghost Drum’ is drawn from the Russian tradition. With

its sequels ‘Ghost Dance’ and ‘Ghost Song’ (now all available as e-books) it is set in “a far-away Czardom, where the winter is a cold half-year of darkness.”

Here we meet the witch-girl Chingis, daughter of a slave, rescued and raised to be a Woman of Power by a shaman woman, who

exchanges the child for a snow baby and takes her away.

Out in the night, in the snow, stood another house. It stood on two giant chicken-legs. It was a little house – a hut – but it had its

double windows and its double doors to keep in the warmth of the stove, and it had good thick walls and a roof of pine shingles. The witch came running over the snow, and the house bent its

chicken-legs and lowered its door to the ground…

…Then the legs took a few quick, jerky steps, sprang, and began to run. Away over

the snow ran the little house… Its windows were suddenly lit by a glow of candlelight. The hopping candlelight could be seen for a long time, shining warmly in the cold, glimmering

twilight, but then the light was so distant and small that it seemed to go out. All that was left of the little house was its footprints.

Raised by the witch-shaman, Chingis becomes her successor, and eventually goes to rescue young Safa, the son of the mad Czar,

whose father has kept him shut up in a single room for his entire life.

Every moment, day and night, waking and dreaming, his spirit cried; and circled and circled the dome room, seeking a way out.

And Chingis heard.

She heard it first as she slept; a strange and eerily disturbing crying.

Stepping from her body, her spirit grasped the thread of the cry and flew on it, like a kite on a line, to the ImperialPalace, to the highest tower, to the enamelled

dome.

Armed with her wits, her spells, and her grandmother’s proverb: “Whenever you poke your nose out of doors, pack courage

and leave fear at home,” Chingis sets off on a mission that will take her all the way to Iron Wood and the Ghost World. This is one of those books I just wish I had written myself,

although I know I never could have done it half so well. It inverts the terror and evil of Baba Yaga, reinventing her as a shaman with powers allied to nature, stronger and more merciful

than the cruelties of Czars. It’s beautiful. Please read it!

I have written a witch of my own – Astrid, the girl with ‘troll blood’ in the book of that name, 'Troll Blood', the third part of my

Viking trilogy 'West of the Moon'. Is she really a witch, though? That’s what the viking sailors call her, because they fear and dislike her, and it’s true she practises

seidr – the old northern magic (pronounced roughly saythoor). But Astrid – haughty, proud, thin-skinned, damaged and vulnerable – hasn’t had much of a chance in life, and

uses her powers to command what respect and fear she can, since she doesn’t expect love. Whether or not any of her spells really work is left open. I don’t know myself. But I do know

that I have a lot of sympathy for difficult, prickly, deceitful Astrid, and I hope the reader will too.

Lastly, what about the Harry Potter books? And why on earth didn’t I begin with them?

Well, to my mind, the Harry Potter books are hardly about witches at all. They’re about school-children masquerading as

witches. Yes – they go to Hogwarts, which is billed as a school for witches and wizards. Yes, they learn spells. Yes, there are plenty of the trappings of witchery about: pointed black

hats, robes, wands (wands? witches don't need wands, those are for wizards), cauldrons, etc. And yes, Harry and his friends are pitted against a Dark Lord of impeccable

credentials, Voldemort, who undoubtedly goes to the same club as Sauron and Lucifer. But does anyone really believe Hermione Granger is a witch? Top of the class in spells she may be,

but seriously? Are Harry and Ron really wizards? Try mentally lining them up with Gandalf, Ged, and even Dumbledore, and see what I mean.

Wizards may go to school, wizards may study things: wizards are expected to be forever poring over old curling scrolls while the stuffed

crocodile dangles overhead. But as soon as you make witchcraft into something taught in a classroom, for me the magic runs right out of it like water from a bath. I do like the first

three Harry Potter books (with reservations about the rest concerning editing, mainly) – I love the energy and fun and sheer inventiveness of Rowling’s writing. But, along with other witch

school series such as Jill Murphy’s ‘The Worst Witch’ and some of Diana Wynne Jones’ Chrestomanci titles, the witchery seems to me to be there to lend colour and flavour to what is basically an

old-fashioned school story. And none the worse for that. However, and it’s an important point, in these modern books the traditional image of the witch has lost its power. Dress up

Hermione in robes and black hat as much as you like, she’ll always look more like a college girl on graduation day than a minion of Satan.

When I started these posts, I wasn’t sure where they would lead me. But it seems to me that over the past seventy years,

the image of the witch in children’s fiction has changed considerably to have reached the point where a set of books about a whole school full of children training to be witches

fighting against evil can be received by the mainstream with perfect aplomb. And I end on this thought – those earnest people who do worry about the Harry Potter books and the treatment

of witches in children’s fiction, need to learn to look past the shadow to the substance.