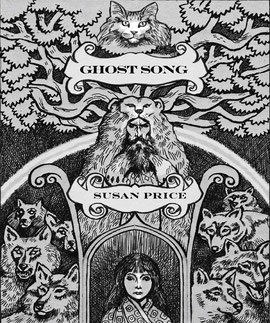

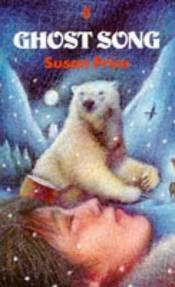

GHOST SONG

Chapter One

A Midsummer Midnight

In a place far distant from where you are are now grows an oak-tree by a lake.

Round the oak's trunk is a chain of golden links. Tethered to the chain is a learned cat, and this most learned of all cats walks round and round the tree continually.

As it walks one way, it sings songs.

As it walks the other, it tells stories.

This is one of the stories the cat tells.

I tell, (says the cat,) of a far-distant, northern Czardom where half the year is summer and light, and half the year is winter dark.

I tell of the strangeness of summer and winter and the Earth's turning. Summer so short, and yet its days so long: one bright day pours endlessly into another and the sun shines at

midnight.

But winter so long, and its days shorten and shorten until noon is dark, and above the snow-covered land the freezing black sky presses down, heavy with the thousands of sharp, glittering stars

and the white, white moon.

The story I tell begins, (says the cat,) in these cold wastes where the moonlight rises from the snow and half-melts the darkness to a silver mist. It begins with the lonely hunter Malyuta

journeying over the snow to look at his traps.

On his left foot was strapped a long ski; on his right foot a short ski, and in his gloved hand he carried a bow, with which he pushed himself along in a fast glide. The wind flung ice crystals in his face, and shook the edge of his big, furred hood with a groan, and, listening to that sad, sad sound, Malyuta thought back across the miles to the village he had left, to his friends and his wife.

They had certainly forgotten him, he thought. In that cold and emptiness he found it hard to remember himself. He felt that he was a ghost, already dead and blowing through endless cold and

darkness in the wind's voice.

Some men could stay warm by the stove through the winter months, but not Malyuta. He was a slave of the Czar - though he had never seen him - and a Czar needs furs. A Czar needs the soft black

furs of sables, and the spotted soft whiteness of ermine; a Czar needs wolf-skins and lynx-skins, and beaver-fur to line his cloak and slippers. He needs these skins so that he can dress himself

in them and feel himself to be a true Czar; he needs them to give as presents to others so that others, too, will believe him a true Czar.

And because of this need, Malyuta had to leave his family every winter to hunt these animals, trap them and kill them and tear off their skins. He was a huntsman of the Czar.

It happened (says the cat) that, in one of his traps, he found a dead sable. He took off his skis and knelt in the snow, looking down at the hard, stiff, frozen little body, lying twisted, as it

had died, with a tight noose about its neck. He saw how intensely black was its fur against the glimmering snow, and how - even in the poor light - the scarlet of its blood flared against the

white snow and its own black fur.

'My first son . . .' said Malyuta, through his heavy, ice-hung beard. Soon he hoped to have a son. 'So should my first son be - black, black hair; black like his mother's hair, black like the

sable's fur. White skin, white teeth, white like the snow. Red lips, red cheeks, red as the blood in them, red as the blood in the snow . . . Black, white and red; sable, snow and blood.'

He spoke his wish aloud - spoke it there, in that cold, dark, shimmering emptiness, where the wind could carry his words for ever. He spoke his wish above the body of a sable that had died in his traps, but he spoke no words to soothe its angry ghost - angry, unappeased, hungry as sables always are.

It is never wise to speak a wish aloud, but to speak it in such a place, in such company - that is to ask misery to live with you.

But whatever misery people wish on themselves, the Earth still turns and, as it turns, the days grow longer and the nights shorter, When the long winter night began to be broken by short, dim

days, Malyuta loaded his sled with his tent and his frozen skins. He harnessed his reindeer to the sled and, with his shaggy, blue-eyed dogs running alongside, he drove over the snow to the city

and the Czar's storehouse. Only after he had delivered the furs, and had been given his reward in food and cloth, was he free to return home.

Malyuta ran alongside the sled with the dogs rather than slow the reindeer with his weight. He helped the reindeer pull the sled over the thawing snow. Quicker, quicker! His mind and his heart

were full of Yefrosinia, who had been his wife for only a year.

Malyuta was not young or handsome and, being a slave, he was a poor man. And so for a long time he had not married, nor had any home of his own. He had spent his winters alone, and the short

summers lodging in the villages owned by the Czar where, as one of the Czar's huntsmen, he could demand shelter. But for many, many years he had wanted a wife, and children. What is a huntsman

without a wife? When he goes away into the winter darkness, who is there to remember him if he has no wife? Who is there to call him back into the firelight of the house, back to summer, once

more? And if a slave has no children, what is he? A slave's only riches are his children.

But Malyuta had never had the courage to ask a woman to marry him until he saw Yefrosinia. He was not young, and nor was she. He was not handsome, and she was not pretty. He had nothing and she,

being the plain, eldest daughter of a slave who worked the Czar's land, had still less. So he had asked her to be his wife, and she had gladly said yes.

And when Malyuta's sled was dragged into the street of the village, over the last of the melting snow, Yefrosinia was waiting for him, wrapped in a big shawl. Whatever beauty Yefrosinia had - in

the darkness of her long hair, in her dark eyes - Malyuta saw it as she stood there in the snow, And when she saw Malyuta, his broad square head fringed round with thick, fair beard and thick,

curling hair, she thought he looked more like a shaggy square-headed terrier than ever. He should bark, she thought, as he came up to her.

'I have good news for you, my old dog,' she said, tugging his beard. 'I am going to have a child.'

Malyuta hugged her tightly, and kissed her and, that night, got very drunk, to celebrate both his home-coming and the child to come - who, he was sure, would be a son: a black, red and white son.

Summer came, short and hot. The sun's heat lovingly stroked the skin. Children ran naked in the village's dusty streets, and dogs lay panting, and cats lay basking. Women left off their shawls

and stockings. Men stripped off their shirts, and the sun drew water out of their skins as they worked and burned them to leather.

Knowing the time to be short, grass, bright, bright green, sprang from the earth. The trees foamed with blossom and were buzzed through by bees. Flowers spread their petals beside every path,

beside every stream, even on the roofs of the houses. In the fields vegetables spurted green leaves and rye grew bearded.

Sheep lambed, cows calved, birds nested and layed. In the streams small fish teemed. In all this heat and life no one, not even Malyuta, could remember how cold, how dark, how barren, winter

was.

And then the child of Yefrosinia and Malyuta was born - at midnight, in the first moments of Midsummer's Day, which is the longest day of the whole year, the day when there is no second of

darkness.

The men of the house were made to sit outside, in the white night, while the baby was being born. They sat on the wooden bench that ran along the front of the hut, and drank, and laughed, and

those with children told stories of their children's birth and babyhood. Malyuta sat among them, blushing, proud that he was soon to be a father at last, but afraid that something terrible would

happen: that Yefrosinia or the baby would die.

When a smiling woman came to the door to call the men in, Malyuta was the first on his feet and the first into the house. He went straight to the bed, smiling a huge, foolish, tearful grin as

soon as he saw that Yefrosinia was well and was smiling back at him. He lowered his weight carefully on the bed, afraid of hurting her, and kissed her, in love and gratitude.

Yefrosinia’s mother came near, with the newborn baby in her arms, and offered it to Malyuta. ‘A son,’ she said, and Malyuta goggled at her.

Trembling with all the joy and fear and wonder that he felt, Malyuta took the baby in his arms. His son had an ugly red face and a fuzz of black hair on the top of his head. Gently, very gently

and carefully, Malyuta lowered his big clumsy head and kissed the baby’s forehead. His beard prickled its face and made it cry, and everyone else laughed aloud – a great noise in the wooden

house.

Startled by the laughter, Malyuta looked up, with tears in his eyes. Then he laughed himself, and laid the baby beside his wife. He held her hand and looked at her, unable to speak, and shaking

his head continually as the tears ran down his face. And she smiled too, tired though she was, to see her big old terrier so happy.

A slave’s children are his only wealth. Well, now, Malyuta thought, he had the first coin in his purse.

It was midsummer and there was no darkness to send the people to bed, so they celebrated the baby’s birth, fetching wooden cups and plates, pouring beer, calling neighbours. The neighbours came carrying food with them. There was eating and drinking, and many toasts to Yefrosinia, to Malyuta, and to the new little boy. Malyuta carried the baby around to everyone, his face red with pride at being a father at long last, when he had begun to think that he would die without a son to leave in the world behind him.

So Midsummer's Day passed; and the evening was as bright as the morning. When the people, tired out, wanted to go to bed and sleep, they had to cover the windows with shutters to make it dark

inside their houses.

Soon only Malyuta was left awake. Despite all that he had drunk, he couldn't sleep. He was too excited, and too afraid.

It was dark inside the house, but the summer light shone through the cracks around the shutters in long, dust-shimmering beams of white light that made the shadows darker. It was hot, too, and

the heat brought the scent out of the wooden walls, and added it to the heavy scent of beer and food.

Malyuta sat on the edge of his wife's bed and watched her and the baby sleep. His thickly hairy legs were bare, because he had taken off his clothes, ready for bed, even though he had no wish to

sleep, and he was dressed only in his shirt. He was thinking long, muddled thoughts. Again and again he bent low over the baby, holding his own breath, to make sure that his son still breathed.

He could not believe that something so tiny and new could breathe all by itself.

I now have all I have ever wanted, he said to himself, and the thought stunned him, and made him afraid. I am no longer the traveller who comes to stay in the village, the lonely man. Now I, too,

have a wife, and a son. I belong here: this is my village because it is my wife's village and the place where my son was born. And what a son he is and will be! Already he has black hair. Black,

white and red he'll be: sable, snow and blood - how can he help but be a great hunter? He'll be handsomer than I ever was and all the women will be eyeing him. I'll teach him how to make a living

even when the snow is five feet deep. And when I have to leave this world, I'll leave him behind me, filling my place and his own. 'Ah, your old grandad,' he'll say to his own children. 'Old

Malyuta, he was a one!'

Again he bent to make sure that the baby was breathing. He looked at his son's little body, no longer from head to foot than his own forearm. And the baby's small mouth and nose, that breathed

for him just as well as Malyuta's great gape and hooter; his little closed eyes. His tiny hands and - smaller and smaller - his tiny fingers, each with a tiny, perfect nail. And this smallness

would grow to Malyuta's size!

Now I believe what they say in the churches, Malyuta thought. I believe that water was turned into wine, and that five loaves and two fishes fed five thousand. If a wonder like this boy of mine

can come from two plain folk like my wife and me, then I believe that miracles are true.

He jumped then, for a blow was struck against the outer door of the house, as if the wooden door had been struck with the end of a heavy stick. The dull noise quivered between the wooden house

walls, and Malyuta got up angrily from the bed, thinking that the noise would wake his wife and baby. But none of the sleepers in the house stirred at the noise, not even when a second and a

third blow were struck before the reverberations of the first had died away.

Malyuta reached for his trousers, and took his long knife from the sheath on his belt before going to the door. It was probably only a neighbour but his love and fear for his wife and new baby

made him tender and sore, afraid of every little thing that might threaten them.

He opened the door of the darkened house and was blinded by the white blaze of midsummer midnight. He raised his hand to shelter his eyes and, from behind it, squinted at the man who stood

outside - a large man, a dark shape against the brightness. Before Malyuta could think or speak, the man moved forward, and moved so briskly and surely that Malyuta stepped back despite himself

and let the stranger into the house. When he quickly turned, his knife ready in his hand, he was blinded by the darkness of the hot, shuttered room.

'Who are you?' Malyuta demanded of the hot darkness. 'What do you want?’

Squinting, he made out the visitor in the middle of the room. The stranger unslung something from his shoulder and dropped it to the floor with a clatter. It was a drum, a flat, oval drum with

strange red patterns painted on its skin. Malyuta's heart gave a jolt. It was a ghost-drum; a shaman's drum.

Malyuta walked towards the visitor to get a closer look. His bare, sweaty feet slapped on the wooden floorboards, stuck to them and peeled away with sucking sounds. The stranger stood still, watching Malyuta come, and grinning.

The stranger had a thin, wrinkled face that peered from a thick growth of grey-streaked black hair and beard. His grin showed large white teeth, and crinkled his face into many fine lines.

Despite the midsummer heat, he was dressed for winter, as if he had come, in a moment, from the far north where it was still cold. Around his shoulders, in heavy, soft, rank folds, hung the

yellow-white skin of a white bear. Its head hung upside-down on the man's shoulders. Its paws, with long black claws, dangled at his sides. Underneath the bearskin cloak the man wore a tunic and

trousers of reindeer hide, decorated with bones, beads, feathers and brass-rings; and so fantastically embroidered that Malyuta's tired eyes were confused by the many intertwining patterns. On

the man's feet were embroidered Lappish boots, and big Lappish mittens were on his hands. A shaman, a night-coming witch - for however brightly the sun shone outside, it was night, white

midnight, the last hour of Midsummer's Day.

'I have come for my child,' said the stranger.

'What child?' Malyuta asked, though he both knew and dreaded the answer.

The witch turned towards the bed where Yefrosinia slept, his heavy boots padding softly on the floor like a bear's paws. But Malyuta, with a jump, reached the bed first and took the baby up in

his own arms.

'My son,' he said. 'My child.' As he spoke, he looked into the witch's sharp face, and saw the bright sunshine of midnight shining through the still open door, and smelt the

scent of grass on the breeze that blew into the house. And he was struck with the certainty that he was dreaming. He had never seen a witch while he was awake. He could give his son to the witch

and it wouldn't matter because it was only a dream.

But whenever he had had such frightening dreams before, Malyuta had woken. Could a dream so fill his nostrils with such a rank smell of wild bear? In a dream, would the beams of sunlight be so

bright and so hot as they moved over the wrinkles of the witch's face? Would the witch's rough voice buzz so in his ear?

The witch poked his head forward and looked into Malyuta's face with eyes as black as a bear's. 'My apprentice born. My child. Give him to me.'

Malyuta shook his head.

The witch grinned like someone who knows he will have his own way in the end. 'Keep him, and he will be the slave of a Czar. He will labour, and suffer, and in a few years he will die. Give him

to me and he will be freer than your Czar. I will teach him the ways to and from the Ghost World and make him a shaman. I will give him three hundred years of life. If it's him that you love, and

not yourself, give him to me.'

'No,' said Malyuta.

'Give him to me. You need not fear blame or punishment. I will give you a baby of mud to put in his place, and you can say that the baby died.'

'I don't fear punishment,' Malyuta said. 'I want my son!'

'Women are not so selfish as men. Your wife would give him to me.'

'Let my wife sleep! I am the man, and I have the say. If it is selfish to keep my own son and guard him, then I am selfish! If you want a son, witch, then get your own!'

The witch sighed and turned away from Malyuta to walk towards a wooden bench on the other side of the room. He walked through bright, narrow beams of light, and through deep shadows. His heavy

boots padded on the floor, and the bear's claws on them clicked. The edge of the bearskin cloak dragged on the floor with a tiny whispering sound, and a rank bear stink drifted from it to

Malyuta's nose. He heard beads and brass-rings rattle on the witch's tunic, and through the open door came the scent of summer flowers and bright white light to drive the shadows into

corners.

'The children born of our bodies are not ours,' the witch said. 'Shamans know that. We know that only those reborn from the Ghost World for our teaching are ours, and they may be any man or woman's child . . . In the Ghost World, my friend, grows Iron Wood where all but shamans lose their way . . . And at the centre of Iron Wood grows the Iron Ash. That tree is so big that animals live on its branches, roaming as widely as they do in this world. Those animals feed the shamans who nest in the tree, waiting to be reborn. It was the sables running about the Tree who told me of my apprentice's birth - '

'The sables!' said Malyuta.

The witch nodded. 'That child you hold has been one of us already. He has been reborn to be one of us again. He is my apprentice. I must take him away before the first day of his new life is

over. Give him to me.'

A great shock had gone through Malyuta when the witch spoke of sables. He had remembered kneeling above the dead sable in his trap, and the wish he had spoken then. An even greater dread of the

witch came over him. 'No!' he said.

The witch rose angrily from the bench and came towards Malyuta, banging his stick on the floor with a loud noise of wood striking wood. Malyuta backed from him, holding the baby.

'I am two hundred and thirty-four years old,' said the witch. 'For two hundred of those years I have waited for this child to be born - my child! I am a master of the three magics; I am

the harvester of ice-apples. I can heal and I can harm, and I can teach all these things. What can you teach?'

Backed against the wall, Malyuta said, 'I shall teach him to hunt.'

'You think that a great thing. Can you teach him to hunt as a bear? Give him to me.'

'I shall teach him to hunt bear!' Malyuta held the baby with one arm and pushed the witch away with the other. 'And until he is big enough for that I shall be a roof to him, a fire for him, a dog

to guard him, a wall against the night. I shall never give him to a night-comer, a Ghost-World Walker!'

The witch swung about and returned to the wooden bench. 'When this hour is over, I must go. So let us talk like men at market, Malyuta - yes, I know your name. What can I give you in exchange for

your child? What do you want more than him? Do you want to be rich, Malyuta? Do you want enough money to buy your own freedom and your wife's? Then you can sell your furs for your own profit and

make yourself rich, and you can get ten sons to replace this one!'

Malyuta felt as if he had been punched, for he knew that the witch could do what he said, and make him a free, rich man. He knew that he could have anything he demanded in exchange for the baby

he held - and it was only a baby. Weren't there enough babies in the world? He felt that his arms would move to hand the baby over and, angry with himself for being tempted, he shouted, 'I am no

Czar, to buy and sell my children! I have also waited a long time - too long - for this one son, and nothing will buy him from me! If you promised to make me the Czar, I wouldn't give him to

you!'

'Is that what you want?' asked Kuzma. 'To be Czar?'

Malyuta's mouth opened and stayed open, and his heart almost stopped as he saw himself as Czar, God on Earth, owning all, ruling all. But he said nothing.

'Would you like to be young again?'

Malyuta held his breath and choked over that offer, and the witch grinned, sure of winning. But Malyuta looked at the midnight sunlight on the rafters, glistening in rainbows on the cobwebs that

hung there. He looked at the northern witch sitting on the plain wooden bench, and the ghost-drum lying in a beam of sunlight on the floor. Outside a cow mooed and a bird sang, and about every

sight and sound there was the very flavour of a dream. So what did it matter what the witch offered? 'Nothing you can give me will buy my son.'

The witch, too, looked towards the open door, where the midnight sunlight was growing stronger. He rose and came towards Malyuta, his feet padding, his cloak whispering and stinking of bear in

the hot room. 'You keep this child because you think he will bring you happiness - but I tell you, not! What you hold there, in your arms, is pain! He is a shaman, a world-walker, a child of the

Iron Ash. He was not meant to be a slave's son, fixed in one world. I tell you, little man, keep him, and you will lose all that you most value. Black as winter darkness; white as ice; red as

blood indeed. Sharp as a sable's bite! He will bring you misery!'

Afraid, Malyuta cried, 'Don't try to curse me!'

'To tell the future is not to curse. Give him to me!'

'No,' said Malyuta, glancing towards the door again, where the light grew brighter and brighter. 'I will never give him to you, not in a dream, and not waking. No matter what you promise, or how

you ask, or how you curse. Not for his sake, not for my sake, not for his mother's sake. He is my son, and I shall rear him.'

'Give him to me!' cried the witch, and laid both his strong mittened hands on Malyuta's shoulders, grinning with anger in his face.

'No!’

Now the witch laid his hands on the baby. 'Give him to me, give him!'

'I would sooner give up my own head than this baby!' Malyuta said.

The witch took his hands from the baby and drew back. The sleepers in the room moved in their places, and sighed. The last moments of Midsummer's Day were passing.

'Two hundred years I've waited for him,' said Kuzma. 'You will have other children; I can have no other. Give him to me.'

'No!'

Midsummer's Day had passed. The witch stooped and picked up his ghost-drum from the floor. In his thick, bear-clawed boots he crossed the floor and went out at the door.

Malyuta raised the baby to his shoulder, put his hairy cheek to the baby's soft one, and let tears of relief run down his face.

Around him, the sleepers were waking, throwing back their covers and sitting up. Still Malyuta didn't know if he was awake or asleep and dreaming.

'Malyuta's rocking the baby!' people said. 'Have you been standing guard over him all night, Malyuta? Ah, and now he's hungry!' they said, as the baby woke and screamed in Malyuta's ear.

Malyuta was silent. His head was heavy and dazed. He thought he'd slept and dreamed. A bad dream. A voice, demanding, demanding, stirring the dust between the wooden walls . . . but he couldn't

remember what the voice had said. He laid his baby son beside his wife and lay down with them to sleep.

Ambrosi, he thought, as he drifted into sleep. I shall call him Ambrosi, because it means 'immortal' and so my son is: he's perfect and, to me, he'll live forever.

-*-

And that, (says the cat,) is how Malyuta the Czar's huntsman defied the bear-shaman and denied him his apprentice.

It is never a lucky thing to do (says the cat), to make an enemy of a shaman.

________________________________________________

Ghost Song' can be downloaded from Amazon kindle books for £1.71 or $2.99.

Or bought from Susan Price's Amazon store.

For other stories and extracts, go here