CAISHO BURROUGHS

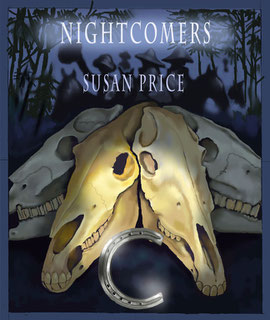

From the book NIGHTCOMERS - available for download now.

During the reign of the first Elizabeth, there came to London and the court a youth named Caisho Burroughs. He quickly became famed for his unusual, even extraordinary, beauty.

His legs were long and well-shaped, his waist small, his shoulders wide, his hair thick and shining; and his face so striking, with

such fine eyes, such a pleasing mouth and white teeth, that everyone, men and women, stared after him in amazement that such a vision should walk, eat, spit, curse and fart.

If the fame of his beauty were not enough, he was soon as well-known for his quickness to see offence in the least remark or gesture;

and for his vengeful temper, difficult to soothe. He had not been in town a year before he had fought three duels, though duelling had been forbidden by Royal Order. With sword in one hand and

dagger in the other, he wounded all three of his opponents, and came near to killing the third.

If the Queen was displeased, she was not more so than Caisho's father, and Caisho was packed off to Italy, to the city of Florence.

Old Burroughs told his friends that he intended his son to see something of the world, and learn to speak Italian, but it was plain to all that his purpose was to keep his lovely but

discreditable son out of the town's gossip for a while.

Many who knew Caisho predicted that he would soon find his way into the gossip of Florence; and so it proved.

At that time the Duke of Florence kept, as his mistress, a certain buxom, beautiful and talented lady named Giovanna.

Though no longer a girl, she was much younger than the Duke, and far from faithful to him. She was amusing herself by watching the

people pass in the street below her window when she saw Caisho, with his pale English skin and his fair hair shining in the sun. So taken with him was Giovanna that she sent her maid running

after him, to fetch him to her.

After that day, Caisho often visited the lady, in secret, and Giovanna grew greedy for him. As often as he came, she wished him to

come again: even on days when the Duke also visited her. Many a time Giovanna's maid let Caisho out of the side door as the Duke was entering at the front - or let Caisho in as the Duke was

leaving.

And yet Caisho gave the woman little enough reason to love him. With his beauty, the appeal of his foreignness, and the charm of

manner he could use when he chose, he was soon run after by both women and men. 'There are many, many womens,' he told Giovanna, 'more pretty as you, and more younger - ' and see, this one had

given him a pearl brooch for his hat, and this one a sapphire drop for his ear . . .

So foolish was Giovanna in her love that she too made Caisho presents of money, and gifts of jewels and clothes. She ran through her allowance from the Duke, and would have been afraid to ask for more for herself - but was more afraid that Caisho would not visit her if she could not lure him with costly bait.

The Duke, when asked for more money, listened to her excuses of having spent too much on new dresses, hats and jewels, and believed

none of them. He knew that she was not faithful to him, but had thought it beneath him to notice her affairs with bakers, gardeners and priests. She wasn't his wife, after all. But Giovanna had

never made lavish gifts to her other lovers. Rather, it had been they who brought gifts to her. As did the Duke himself.

The Duke accordingly made enquiries among his acquaintance, and soon heard more than enough of the frequent visits to his mistress by

the young Englishman, Caisho Burroughs.

And more than enough of the gold coin and gold chain, the brooches and finger-rings, the point-laces and shoe-buckles, the silks and

velvets and brocade which Giovanna had given him.

The Duke had heard gossip of Caisho, and had even seen him when Caisho, as was courteous in a foreign visitor, had attended the Duke's

court. The Duke had been struck, as was everyone, by the Englishman's beauty but, having no taste for young men himself, the Duke had not seen him since. Now, however, a certain ardour was lit

within the Duke concerning Caisho, and he set spies to watch.

When the spies reported to the Duke that Caisho had entered his mistress' house only minutes after he had left it himself, he was

affronted and furious. Seeing Caisho again, at court, his fury grew, for Caisho was taller than he; and the Duke was losing his hair and gaining a paunch. In short, the Duke fell as deep in

jealous hatred of Caisho as Giovanna had fallen in love. But the Duke had a cure for his ill. He ordered Caisho's murder.

It was Caisho's good fortune that, among the Duke's friends was a man who loved Caisho, and had given him presents and done him many

favours, though never receiving more in return than a smile, and thanks spoken in poor Italian. This man could not bear to think of Caisho's beauty spoiled by a knife, and thrown into the Arno as

carrion. Risking his own life, he warned Caisho of the Duke's intention, and even helped him to leave Florence. Caisho, smiling, thanked him in poor Italian, and then, being tired of Italy, made

his best speed out of that country and into France. He travelled the faster for having left most of his luggage behind.

II

The Duke of Florence, when he discovered Caisho's escape, turned all his anger on Giovanna, raved at her and beat her, and told her that her cowardly lover had run away, caring more for his own

hide than for her spoiled charms. She, in terror of the Duke, and despairing at the knowledge that Caisho had never loved her, and that she would never see him again, took a dagger and stabbed

herself to death.

Caisho was ignorant of Giovanna's death, but nor did he stay on his journey to allow any news from Italy to catch him.

Reaching the Channel, he took ship for England, then bought a horse and rode to London. On arriving, he was pleased to find his younger brother, John, staying in his lodgings. He immediately made

his brother presents of a brooch, chain and thumb-ring which had been given him in Italy.

They went out together to dine and, at the eating-house, met old friends, who gathered to the brothers' table and drank to Caisho's return. Because they admired the costly and foreign jewels he

wore, Caisho gave to one the sapphire drop from his ear, to another the pearl brooch from his hat, and to others rings and chains. He could not remember with any certainty who had given them to

him. The only things he had from Italy with which he would not part, no matter how they were admired, were a matching sword and dagger of the finest, deadliest manufacture. They had been given

him by that same man who had helped him escape from Florence.

Long after dark, drunk and tired, the brothers returned home and, there being only one bed, they climbed into it and fell asleep side by side.

A woman's voice woke them, calling, 'Caisho!' Raislng themselves, they both saw, standing at the bed's foot, a woman dressed in loose white robes. Against the darkness, and her long black hair that mingled with it, her face showed still whiter than her linen, and from within blue shadows her dark eyes stared and stared as if she could not move or close them.

She stared at Caisho.

Her eyes held the brothers in silence and stillness. She fumbled at the neck of her shroud with blue-fingered hands and pulled it

open. They saw her white breasts, disfigured with open wounds. Caisho, who had seen those breasts when they were warm and beautiful, trembled so hard that he shook the bed beneath them.

Through stiff jaws, with difficulty, the woman spoke, on a sigh, like the sigh that will often escape a corpse. She said:

'Cai-sho.'

That word only: and between one blink of the eye and the next, she was not there. Caisho fell back on the pillow. John jumped from the

bed and ran to the spot where the woman had stood. Nothing was there but a cold that made him gasp.

The cold, and the darkness of the room, which still whispered with the apparition's sigh, set him shaking, and he scrambled back into

the bed, where he pulled the covers over the heads of both himself and Caisho. Through the rest of the night he lay awake, shuddering, and clinging tight to Caisho's senseless body.

Bright morning came, and calmed the worst of John's fear. He even began to think he had dreamed the night's terror. But when Caisho

woke, he had dreamed the same dream.

From that day to the end of his short life, Caisho knew no peace.

Even in a friend's lodgings, he could not bear to have the door of a room stand open, because of what might slip through it behind his

back. But nor could he bear a door to be shut, for fear of what might be standing, unseen, on the other side.

Many, many times he was seen to turn, with a start, to look behind him. His own mirror he threw away, and he could not abide a mirror anywhere he was, but would jump up and turn it to the wall, because of what he glimpsed reflected there.

John, anxious for his brother, made sure he was surrounded by friends, but the liveliest company brought Caisho no ease, for he was

constantly counting the people present. No assurances, no lighting of more candles, nor even the shining of those candles into every dark corner, could rid Caisho of the notion that another had

come in, unnoticed, and was standing or sitting among them.

Caisho feared even crowded streets in daylight, and walked with lowered head, fearing that, if he raised his eyes, it would be to look

into her stare.

It was a week after the dead woman's first appearance that Caisho and John were at dinner among friends. Caisho had been silent, as he

now always was, but broke through the talk with a loud and quavering cry. His alarmed friends, looking where he did, saw a woman standing in a shadowed corner, her long black hair melting into

the darkness while her white face and shroud shone lividly, like the moon in a dark sky. She neither spoke nor moved, but stared on Caisho with a fixity until she vanished.

After that, the appearance of the ghost was foretold by the colour blanching from Caisho's face, leaving it grey and cold as clay. He

would sweat, and shake with such violence he could neither stand nor even sit on bench or stool unless he was held by others. His teeth clashed. His eyes fixed themselves on some patch of empty

air, and he cried out, 'She comes! Oh God, she comes, she comes!' Visitors who feared to see the apparition would hurry to leave, for next the dead woman, glaring, would appear where Caisho

gazed.

Caisho's friends soon fell away, even those who had accepted from him pearls, sapphires and table-cut diamonds. With many, it was not

fear of the ghost that made them stay away, but fear of Caisho. The haunting made him yet more tempersome, and he never left his rooms without belting on the Italian sword and dagger. He had even

drawn on his brother John, though a moment later he had thrown his own arm across his eyes and turned away.

III

It happened that, as John and Caisho were one day making their way to an eating-house, almost a month after the ghost's first appearance, a stranger jostled against Caisho, and knocked him into

the filth of a brook, soiling his boots. Though the man apologized, Caisho would not accept, but pushed the quarrel and pursued the man even with John hanging on his arm, and spoke with such

contempt that the man at last could do nothing but agree to meet Caisho at first light in the open fields nearby.

It was John who lay awake that night while Caisho, exhausted, slept, though he woke suddenly before dawn. He started to dress for the duel, but his hands shook so he could not fasten buttons or tie strings, and John went to help him.

'Send word that you withdraw,' John begged. 'Fight not today: you are nowise fit for it.'

'Never,' Caisho said, and shuddered, and stared with fixed eyes at the corner behind John's shoulder. John hugged him tight, but

couldn't contain the trembling: and trembled himself when the woman appeared, white face and white shroud, from the corner's darkness. She held out stiff arms. Staring from a white, stiff face,

she made a kissing mouth with blue lips, and was slow in her fading.

They were late for the meeting, but John could not keep Caisho from it. The other man, when he saw Caisho's pale face and the tremors

that still ran through him, thought him sick and offered to withdraw. But Caisho called him coward, and a nothing; a cock who crowed from a dunghill but had no belly for the fight; a craven,

pigeon-hearted runagate. All the while he advanced on the man with his sword and dagger drawn, making passes with them until, between shame and anger, the man took up his own weapons.

Caisho's attack was fierce, and put his opponent in fear for his life as he desperately sought to block blows from both the sword and

dagger. He lost many chances to strike a blow himself through fear that, in doing so, he would feel the Italian steel enter him. But, growing desperate as he tired, he lunged - and nothing

blocked his sword but Caisho's heart.

John ran to Caisho, and knelt over him, but Caisho, with fixed eyes, looked through him and beyond him. John, turning his head, cried,

'Oh God, she comes! She comes!' But there was no woman in the duelling field. When John turned back to his brother, Caisho was dead, and his great beauty already in decay.

With apologies to John Aubrey, who first reported Caisho Burroughs' story, as true, in his 'MISCELLANY'. The above is

loosely based on it, from memory.